Image 1 of 2

Image 1 of 2

Image 2 of 2

Image 2 of 2

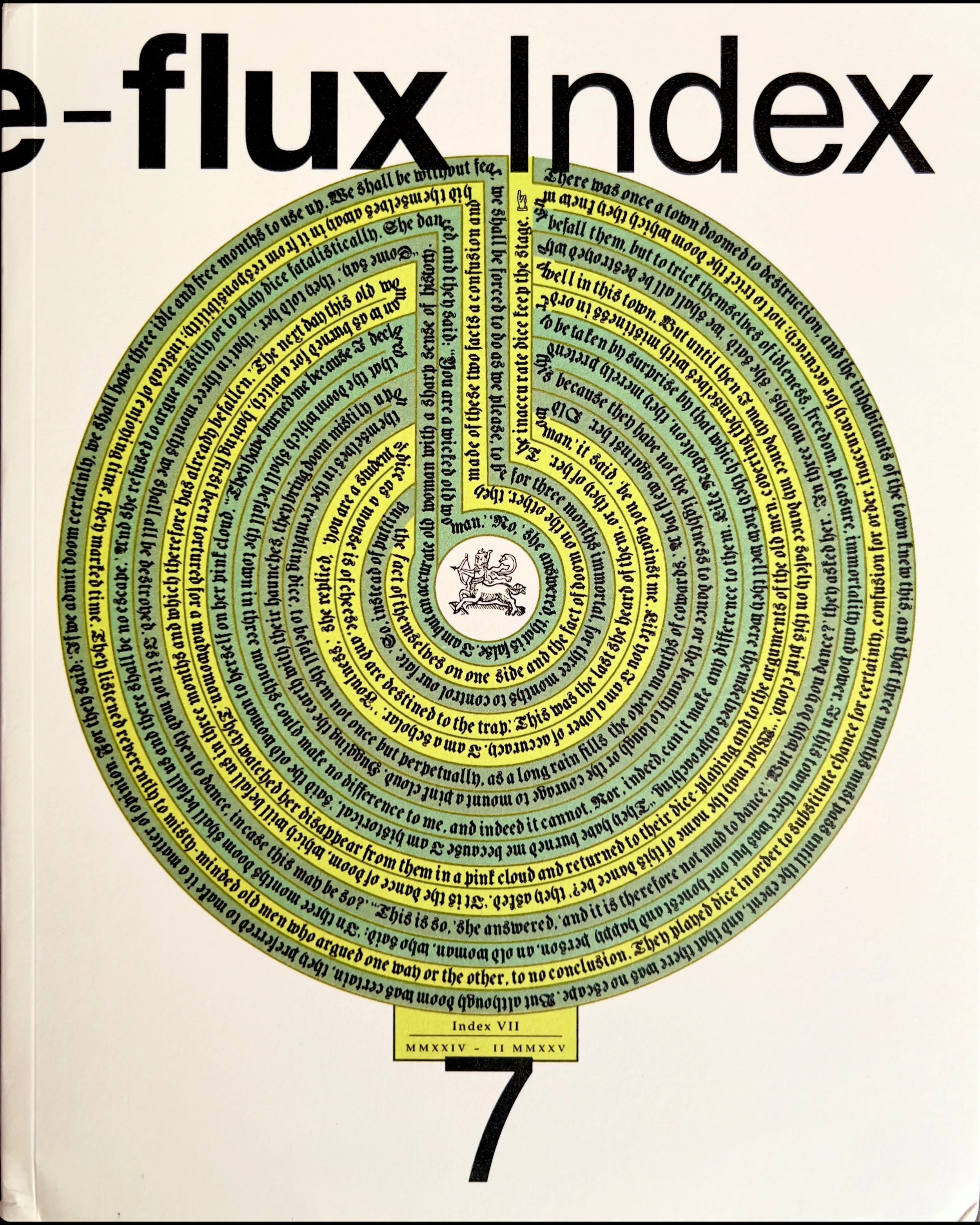

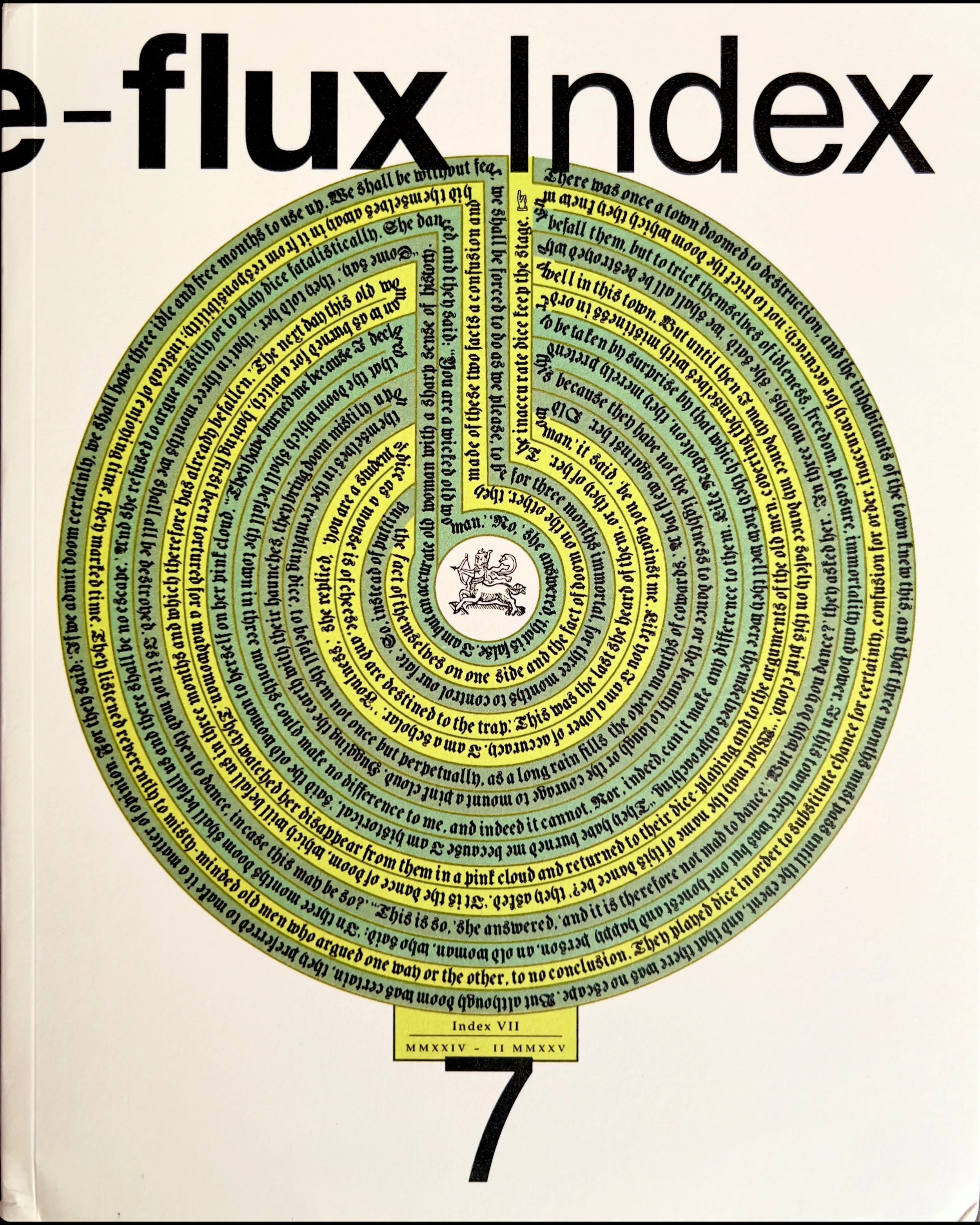

e-flux Index #7

e-flux/584 pgs

Excellent condition

_____________________________________________________________

As we myopically gaze at the handsets inches from our face, we are often encouraged by sensible apostles of “objectivity” to try and get some perspective; to zoom out, zoom up, and achieve something like a lofty bird’s-eye view on our situation.

The first moderns to attain this kind of vertiginous perspective did so at the risk of their own death. The pioneer of aerial photography is generally agreed to have been an eccentric cartoonist and balloonist called Felix “Nadar” Tournachon, who constructed a 60-foot hot air balloon he christened Le Géant, complete with an onboard dark room, to soar above Hausmann’s Parisian boulevards in the 1860s. Though his aerial photographs no longer survive, Nadar’s promethean ascent in his “giant” and the new perspective it augured captured the imaginations of everyone from Jules Verne to Honoré Daumier. Subsequent pioneers of aeronautical imaging, from Jules Neubranner’s Bavarian Pigeon Corps to Alfred Nobel’s rocket-mounted cameras in the 1900s, all intensified this ecstatic drive to escape our terrestrially-bound sightlines, until aerial photography from airplanes became ubiquitous for reconnaissance purposes during the First World War.

With the advent of commercial aviation, the synoptic view over the Earth became ordinary and demystified—something a tourist or businessperson sleepily glimpses through a porthole window before putting on their sleep mask. Yet for several writers, theorists, and artists, the roaming view of our lives from above has retained its mysterious compositional power to bring things into perspective. Take the Scottish painter Carol Rhodes, whose melancholy and enigmatic “edgeland” paintings of depopulated industrial parks, airports, service stations, and agroindustrial monotony are handled with such a deft and enlivening sense of color that they invite us to reflect on the actuality of the modern landscape (rather than its postcard idealization). Speaking on the unique scalar effects of her aerial view works, Rhodes stressed their absence of any orientating horizon line:

I have spoken before of how conscious I am of giving everything a sort of equal status in the pictures, which is enabled by the aerial view, seeing the landscape top to bottom, not near and far. Front doesn’t have priority over middle-ground, middle-ground over background; it’s sort of spatially egalitarian.… When you notice something, really notice it, you’re inside it and outside it at the same time, aren’t you. It’s a paradox. Distance needn’t mean you’re detached.

Meanwhile, for a later writer like W. G. Sebald—whose vision was haunted by the indiscriminate carpet bombardment of European cities during the Second World War, as ours is by the images of Gaza obliterated by indiscriminate IOF bombardment—there was a disquieting eco-pessimism summoned up by this horizonless vantage point on antlike rows of terraced housing and sprawling spaghetti junctions absent of people. As he wrote in The Rings of Saturn (1995):

No matter where one is flying… it is as though there were no people, only the things they have made and in which they are hiding… and yet they are present everywhere upon the face of the earth. Extending their domination by the hour, moving around the honeycombs of towering buildings and tied into networks of a complexity that goes far beyond the power of any one individual to imagine. ... If we view ourselves from a great height, it is frightening to realize how little we know about our species, our purpose and our end.

e-flux Index #7 itself floats upward to give an aerial view over the terrain of everything e-flux published between December 2024 and February 2025. This peek through the porthole across three months worth of daily publishing gathers together long-form essays on contemporary culture and architecture, exhibition, book, and film reviews, profiles of artists, critical interjections, fresh translations from the historic avant-garde, and analytical dispatches from live political and social conjunctures. These have been recomposed into eleven thematic sections, to help us get some perspective (however vertiginous) on the present moment and emergent tendencies in critical discourse. Like Rhodes’ paintings, these sections are also spatially egalitarian, and they refuse the usual hierarchy of ordering texts. They are titled Vegetarians Miss Fewer Flights; Seeking Truth From Facts; Playtime; The Form Was Simple; Hardcore Diaries; Scratching on things I could disavow; Chronotopes; Walls of Complexity; Wet Concrete; We Want Everything; and They Are Shutting Off the Lights. Enjoy the flight!

**

This issue begins with Vegetarians Miss Fewer Flights, a section on prediction and possibility. In December 2024, Google incorporated its Gemini AI into search results, supplementing the slight exertion of critical discrimination needed to scroll that bit further down and choose a hyperlink with a potted (and often spurious) summary instead. Resisting this automated short circuiting of critical thought, in this section Sven Lütticken begins by asking: What potential does the concept of potentiality still hold? What can prediction and pattern recognition promise when the “Stochastic Parrots” of Silicon Valley’s AI chatbots employ such tools only to churn out vast quantities of high-grade slop? R. H. Lossin’s two-part essay interrogates the potential for AI art to effectively model new futures with the master’s tools. Ilan Manouach meanwhile argues that AI’s true potential can perhaps only be glimpsed by reckoning with its composite, hybrid, and distributed qualities. Other modes of virtual thinking can be found in Charles Tonderai Mudede’s theorization of the “configuration space” informing W. E. B. Du Bois’s insights into racial capitalism, in Agnes Arnold-Forster’s reconsideration of the postwar British welfare state (and its planner’s) means–ends calculus of likely scenarios, and in Krzysztof Kieslowski’s reflections on his film Blind Chance (1987).

From possible worlds, the Index then takes a hard U-turn to examine the facts. In Seeking Truth From Facts we enter the sober world of blind contingency, information, facticity and thrownness, things that are given and just as readily taken away—facts that care not one jot about our feelings. Jacob Dreyer explores how scientific facts are prioritized and constructed under the current regime of Chinese techno-science. Nilo Goldfarb asks how 1960s refuseniks such as Fred Lonidier sought to reinvent the documentary form on a Californian campus. Jason Read enters into the mythocratic imaginary of the new right, and their tidy simple fictions of “what is happening and what is wrong,” while Ben Eastham exalts the mischievous blurring of fact and fiction in Kevin Killian’s “New Narrative.” We read of how Rainer Werner Fassbinder dealt with the raw facts of translating Genet’s Querelle to the screen, how Augustas Serapinas’s irreverent contextual constructions dramatize the myth of the given, while Daniel Belasco shows how the Arts Students League cultivated a social realist art appropriate to the multiple crises of America in the late 1940s.

In Playtime the games begin. Holy Fools vs. Tricksters vs. socialist RPG enthusiasts. The game designers Yin Aiwen and Yiren Zhao write on the difficulties involved in using simulation games as “investigative architectures” to model decentralized futures, while at Steirischer Herbst 24 Nikolay Smirnov perceives how the struggle for an emancipatory popular art form alights upon political comedy. The cooperative and open spirit of childhood play Alan Gilbert identities in Francis Alÿs’s video work finds its warped, funhouse reflection in Max Grünberg’s essay on the tensions between competition and solidarity, particularly that closed war game par excellence: chess. In his conversation with Daniella Brito, the filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris celebrates the Trickster as an irreverent archetype present across African diasporic cultures (from Haitian Vodou to Br’er Rabbit), while Travis Diehl’s review of a recent Michael Asher retrospective highlights the puckish, wily tenor of so much of Asher’s site-specific work.

Though “formalist” remains a slur for many, the looming Question of Form continues to cast a long shadow across artistic, architectural, and theoretical discourse. The Form Was Simple commences with a conversation between Kristin Ross and Andreas Petrossiants on the postcapitalist form of the Commune, which opens out onto a larger investigation into the orientating axis of the “subsistence perspective” within contemporary experiments of communal living. Two contributions from an ongoing e-flux Architecture project titled Treatment (by Reinier de Graaf and Alex Retegan, and Stanislaus von Moos respectively) interrogate the formal typologies of modernist approaches to hospital construction (“the matchbox on a muffin”). The material affordances of disorganization and the informe appear in Thotti’s review of the neo-concretist Carlito Carvalhosa and in Innas Tsuroiya’s reading of the tussle between modernism and tradition in Ahmad Sadali’s calligraphic paintings. Three unearthed reflections on early avant-garde filmmaking from Le Corbusier, Kazimir Malevich, and Sergei Eisenstein meanwhile tessellate, respectively, the question of film’s medium-specificity, its formal plasticity, and its capacities for generating new truths.

The end of the year 2024 marked the passing of a decade of Ukraine’s uninterrupted exposure to and work with the “hardcore” material of war. Hardcore Diaries presents, in toto, a selection of essays from e-flux Architecture’s Reconstruction project published in December 2024, edited by Michał Murawski, Kateryna Rusetska, and e-flux Architecture.These pieces explore the challenges of rebuilding during wartime. As their editorial clarifies:

Ukrainian grassroots reconstruction initiatives have sifted through, cleared up, and re-used bricks, rubble, and ruined matter. They have worked in collaboration with and in response to the real needs of communities affected by war, in order to piece together both the immediate foundations and the long-term structures of lives and worlds. Members of these volunteer initiatives have an experiential understanding of what it takes to contain and sustain lives, communities, heritage, and ecosystems facing disintegration and destruction. The work of volunteer reconstruction initiatives serves here as a point of departure for reflecting on a variety of collective undertakings that have emerged organically in response to a long decade of crisis, upheaval, and war. What new social, spatial, economic, and ecological formations, the experiences of the Ukrainian hardcore inspire us to speculate, may emerge from the rough ground of war?

Moving from the intense and brutal locality of the previous section, in Scratching on things I could disavow we spin the globe. When the imperialist, Occidental anchoring of the world is displaced, purported centers and peripheries become recalibrated and everything starts to shift and multiply (as in Nolan Oswald Dennis’s distinctive globe sculptures, mentioned here in Sean O’Toole’s artist profile). The new “intense proximities” produced by globalized supply chains and labor flows redraw the maps of what was once quaintly termed the global village, as is discussed in Émilie Renard, Claire Staebler, and Mathilde Walker-Billaud’s conversation on Okwui Enwezor’s 2012 Paris Triennale. Yuk Hui examines how the neoliberal order’s favorite lexicon of societal transition, development, and progression under the auspices of free trade rings hollow against a neo-reactionary recurrence in the political centers of the former West, while a conversation on Mohamed Amer Meziane’s new book The States of Earth illuminates how the imperial violence of extractivism and dispossession has become increasingly integral to the functioning of the modern nation state. Curious entanglements and strange networks abound: from nonhierarchical uncuration in a Jakarta biennial to Syria’s post-Assad futures, from Hegelian philosophers-cum-diplomats negotiating international trade deals to arts educators countering the epistemic racism of the global art world.

Tick-tock. In Chronotopes time goes by, as multiple—and often incommensurable— timescales and calendars intermesh with and overwrite one another. Hallie Ayres writes on the human and non-human records of time passing (in recent work by ikkibawiKrrr), Musoke Nalwoga on the real footage of an event and its subsequent reenactment (in Cihad Caner’s work on a 1972 Dutch anti-immigrant riot), and Leopoldina Fortunati on the marked discrepancy between the male proletarian’s hourly waged labor and the housewife’s unremunerated double shift. Questions of longevity and exceptionality are also chronotopic—here seen in Maria José de Abreu writing about the Portuguese experience of life under Europe’s longest-lasting fascist regime—as are the petrofatalist high-speed chases engaged by Y. Malik Jalal’s assemblage work and the “glitch in the imperial clock” that Xenia Benivolski finds throughout Ho Tzu Nyen’s investigations into imperial efforts to control time.

From the shifting sands of the globalized, post-liberal geopolitical order to the post-genomic framework of modern cancer research, increasing orders of complexity bedevil our current epistemologies. In Walls of Complexity, the more we see, the more perplexed we become. Correspondingly, artists, curators, and radical thinkers continue trying to reckon with the situation Aslak Aamot Helm characterizes—in his essay on complexity in the life sciences—as the “valley of undetermination.” Reviewing a recent Hans Haacke retrospective, Jörg Heiser finds the veteran institutional critic forensically mapping the sprawling portfolio of a New York slumlord, while Stephanie Bailey visits a prismatic conference on the deep time of collective struggle staged within an immersive diorama. For Ben Eastham, the sprawling extent of the latest Sharjah Biennial approaches what Ursula Le Guin called the strange realism of our strange reality, while for Juan José Santos the bewildering combination of familiar if incompatible themes in the 38th Panorama of Brazilian Art starts to feel like a “bureaucratic exercise.”

There is a moment in revolutionary time after the old order is deposed and before the Wet Concrete sets. This is an interregnum when the volatile energies of resistance, refusal, protest, and defance have yet to canalize into political organizations or institutions. Dingxin Zhao’s thoroughgoing genealogy of nationalist movements here situates the wet concrete of the French Revolution as the foundations of European liberal nationalism, while Carmen Amengual’s flms look out toward the dimming 1970s horizons of Third Worldist cultural revolution. Tamta Khalvashi and Luka Nakhutsrishvili’s dispatch from Georgia’s ongoing post-election mass protest movement resonates with Tom Allen’s reading of the concluding volume to Peter Weiss’s epic bildungsroman of political refusal, The Aesthetics of Resistance. Henry Giroux ekes out a space for a critical theory of education, while Valeria Graziano, Marcell Mars, and Tomislav Medak extol the swashbuckling, insurgent activity of “pirate carers.” Finally, a pair of reviews from Stephanie Bailey and Kaelen Wilson-Goldie touch on the artistic meditation of more recent instances of defiance, from the Tunis protests that sparked the 2010 Arab uprisings to the 2019 protests against Bolsonaro’s shoot-to-kill policy in Rio’s favelas, against which the syncretic iconography of Antonio Obá’s paintings can be situated.

From the revolutionary desire for a world turned upside down, in We Want Everythingthe Index turns to examine how (as Proust had it) “Desire makes everything blossom; possession makes everything wither and fade.” This process of blossoming and withering holds for speculative economic bubbles like Tulipomania, explored in Charles Tonderai Mudede’s essay on the nascent capitalism of early modern Netherlands. It also holds for the insatiable new needs produced by the advertising industry (as can be seen in Isabel Jacobs’s piece on Radu Jude’s montage of post-communist commercials in Romania: Eight Postcards from Utopia, 2024). Desire blossoms in the experimental eroticism of Sagarika Sundaram’s textile works and the supple paintings of the MuMoToMo collective. Pietro Bianchi finds repressed desires roaring to the surface in the latest remake of Nosferatu from Robert Eggers, while Crystal Bennes writes on Mohamed Abdouni’s subtle meddling with “male homosocial desire” in a family archive. Orit Gat attends the curious exercise in gallery matchmaking that is Condo London, and McKenzie Wark’s thoroughgoing rundown of last spring’s bumper crop of trans literature touches on the entanglement between disappointment and desire, as well as the joyful busting of cis taboos.

Index #7 breathes its last gasp and draws to a close with a section on health, death, therapy, sickness, aging, sclerosis, contagion, and healing. Titled They Are Shutting Off the Lights, here we anxiously observe noxious chemicals sealed in the glass cylinders of Hamad Butt’s metastable sculptures, stroll along the innovative loggia of Filippo Brunelleschi’s Florentine Ospedale degli Innocenti (Hospital of the Innocents), and in Dresden find Kenny Fries writing on misguided curatorial framing of works by disabled artists. Lydia Xynogala takes to the waters in her genealogy of late-nineteenth century hydrotherapy, while Leslie Chapman takes to the couch with an algorithmic shrink, and Yvan Prkachin takes the time to explore the process of bricolage at work in medical innovation. Amica Dall introduces us to burned-out activists, while Franco “Bifo” Berardi takes the salutary example of the United Healthcare CEO shooter Luigi Mangione to parlay between a generation of terminally distracted youth and the systemic, chaotic dementia of a sundowning political order.

e-flux/584 pgs

Excellent condition

_____________________________________________________________

As we myopically gaze at the handsets inches from our face, we are often encouraged by sensible apostles of “objectivity” to try and get some perspective; to zoom out, zoom up, and achieve something like a lofty bird’s-eye view on our situation.

The first moderns to attain this kind of vertiginous perspective did so at the risk of their own death. The pioneer of aerial photography is generally agreed to have been an eccentric cartoonist and balloonist called Felix “Nadar” Tournachon, who constructed a 60-foot hot air balloon he christened Le Géant, complete with an onboard dark room, to soar above Hausmann’s Parisian boulevards in the 1860s. Though his aerial photographs no longer survive, Nadar’s promethean ascent in his “giant” and the new perspective it augured captured the imaginations of everyone from Jules Verne to Honoré Daumier. Subsequent pioneers of aeronautical imaging, from Jules Neubranner’s Bavarian Pigeon Corps to Alfred Nobel’s rocket-mounted cameras in the 1900s, all intensified this ecstatic drive to escape our terrestrially-bound sightlines, until aerial photography from airplanes became ubiquitous for reconnaissance purposes during the First World War.

With the advent of commercial aviation, the synoptic view over the Earth became ordinary and demystified—something a tourist or businessperson sleepily glimpses through a porthole window before putting on their sleep mask. Yet for several writers, theorists, and artists, the roaming view of our lives from above has retained its mysterious compositional power to bring things into perspective. Take the Scottish painter Carol Rhodes, whose melancholy and enigmatic “edgeland” paintings of depopulated industrial parks, airports, service stations, and agroindustrial monotony are handled with such a deft and enlivening sense of color that they invite us to reflect on the actuality of the modern landscape (rather than its postcard idealization). Speaking on the unique scalar effects of her aerial view works, Rhodes stressed their absence of any orientating horizon line:

I have spoken before of how conscious I am of giving everything a sort of equal status in the pictures, which is enabled by the aerial view, seeing the landscape top to bottom, not near and far. Front doesn’t have priority over middle-ground, middle-ground over background; it’s sort of spatially egalitarian.… When you notice something, really notice it, you’re inside it and outside it at the same time, aren’t you. It’s a paradox. Distance needn’t mean you’re detached.

Meanwhile, for a later writer like W. G. Sebald—whose vision was haunted by the indiscriminate carpet bombardment of European cities during the Second World War, as ours is by the images of Gaza obliterated by indiscriminate IOF bombardment—there was a disquieting eco-pessimism summoned up by this horizonless vantage point on antlike rows of terraced housing and sprawling spaghetti junctions absent of people. As he wrote in The Rings of Saturn (1995):

No matter where one is flying… it is as though there were no people, only the things they have made and in which they are hiding… and yet they are present everywhere upon the face of the earth. Extending their domination by the hour, moving around the honeycombs of towering buildings and tied into networks of a complexity that goes far beyond the power of any one individual to imagine. ... If we view ourselves from a great height, it is frightening to realize how little we know about our species, our purpose and our end.

e-flux Index #7 itself floats upward to give an aerial view over the terrain of everything e-flux published between December 2024 and February 2025. This peek through the porthole across three months worth of daily publishing gathers together long-form essays on contemporary culture and architecture, exhibition, book, and film reviews, profiles of artists, critical interjections, fresh translations from the historic avant-garde, and analytical dispatches from live political and social conjunctures. These have been recomposed into eleven thematic sections, to help us get some perspective (however vertiginous) on the present moment and emergent tendencies in critical discourse. Like Rhodes’ paintings, these sections are also spatially egalitarian, and they refuse the usual hierarchy of ordering texts. They are titled Vegetarians Miss Fewer Flights; Seeking Truth From Facts; Playtime; The Form Was Simple; Hardcore Diaries; Scratching on things I could disavow; Chronotopes; Walls of Complexity; Wet Concrete; We Want Everything; and They Are Shutting Off the Lights. Enjoy the flight!

**

This issue begins with Vegetarians Miss Fewer Flights, a section on prediction and possibility. In December 2024, Google incorporated its Gemini AI into search results, supplementing the slight exertion of critical discrimination needed to scroll that bit further down and choose a hyperlink with a potted (and often spurious) summary instead. Resisting this automated short circuiting of critical thought, in this section Sven Lütticken begins by asking: What potential does the concept of potentiality still hold? What can prediction and pattern recognition promise when the “Stochastic Parrots” of Silicon Valley’s AI chatbots employ such tools only to churn out vast quantities of high-grade slop? R. H. Lossin’s two-part essay interrogates the potential for AI art to effectively model new futures with the master’s tools. Ilan Manouach meanwhile argues that AI’s true potential can perhaps only be glimpsed by reckoning with its composite, hybrid, and distributed qualities. Other modes of virtual thinking can be found in Charles Tonderai Mudede’s theorization of the “configuration space” informing W. E. B. Du Bois’s insights into racial capitalism, in Agnes Arnold-Forster’s reconsideration of the postwar British welfare state (and its planner’s) means–ends calculus of likely scenarios, and in Krzysztof Kieslowski’s reflections on his film Blind Chance (1987).

From possible worlds, the Index then takes a hard U-turn to examine the facts. In Seeking Truth From Facts we enter the sober world of blind contingency, information, facticity and thrownness, things that are given and just as readily taken away—facts that care not one jot about our feelings. Jacob Dreyer explores how scientific facts are prioritized and constructed under the current regime of Chinese techno-science. Nilo Goldfarb asks how 1960s refuseniks such as Fred Lonidier sought to reinvent the documentary form on a Californian campus. Jason Read enters into the mythocratic imaginary of the new right, and their tidy simple fictions of “what is happening and what is wrong,” while Ben Eastham exalts the mischievous blurring of fact and fiction in Kevin Killian’s “New Narrative.” We read of how Rainer Werner Fassbinder dealt with the raw facts of translating Genet’s Querelle to the screen, how Augustas Serapinas’s irreverent contextual constructions dramatize the myth of the given, while Daniel Belasco shows how the Arts Students League cultivated a social realist art appropriate to the multiple crises of America in the late 1940s.

In Playtime the games begin. Holy Fools vs. Tricksters vs. socialist RPG enthusiasts. The game designers Yin Aiwen and Yiren Zhao write on the difficulties involved in using simulation games as “investigative architectures” to model decentralized futures, while at Steirischer Herbst 24 Nikolay Smirnov perceives how the struggle for an emancipatory popular art form alights upon political comedy. The cooperative and open spirit of childhood play Alan Gilbert identities in Francis Alÿs’s video work finds its warped, funhouse reflection in Max Grünberg’s essay on the tensions between competition and solidarity, particularly that closed war game par excellence: chess. In his conversation with Daniella Brito, the filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris celebrates the Trickster as an irreverent archetype present across African diasporic cultures (from Haitian Vodou to Br’er Rabbit), while Travis Diehl’s review of a recent Michael Asher retrospective highlights the puckish, wily tenor of so much of Asher’s site-specific work.

Though “formalist” remains a slur for many, the looming Question of Form continues to cast a long shadow across artistic, architectural, and theoretical discourse. The Form Was Simple commences with a conversation between Kristin Ross and Andreas Petrossiants on the postcapitalist form of the Commune, which opens out onto a larger investigation into the orientating axis of the “subsistence perspective” within contemporary experiments of communal living. Two contributions from an ongoing e-flux Architecture project titled Treatment (by Reinier de Graaf and Alex Retegan, and Stanislaus von Moos respectively) interrogate the formal typologies of modernist approaches to hospital construction (“the matchbox on a muffin”). The material affordances of disorganization and the informe appear in Thotti’s review of the neo-concretist Carlito Carvalhosa and in Innas Tsuroiya’s reading of the tussle between modernism and tradition in Ahmad Sadali’s calligraphic paintings. Three unearthed reflections on early avant-garde filmmaking from Le Corbusier, Kazimir Malevich, and Sergei Eisenstein meanwhile tessellate, respectively, the question of film’s medium-specificity, its formal plasticity, and its capacities for generating new truths.

The end of the year 2024 marked the passing of a decade of Ukraine’s uninterrupted exposure to and work with the “hardcore” material of war. Hardcore Diaries presents, in toto, a selection of essays from e-flux Architecture’s Reconstruction project published in December 2024, edited by Michał Murawski, Kateryna Rusetska, and e-flux Architecture.These pieces explore the challenges of rebuilding during wartime. As their editorial clarifies:

Ukrainian grassroots reconstruction initiatives have sifted through, cleared up, and re-used bricks, rubble, and ruined matter. They have worked in collaboration with and in response to the real needs of communities affected by war, in order to piece together both the immediate foundations and the long-term structures of lives and worlds. Members of these volunteer initiatives have an experiential understanding of what it takes to contain and sustain lives, communities, heritage, and ecosystems facing disintegration and destruction. The work of volunteer reconstruction initiatives serves here as a point of departure for reflecting on a variety of collective undertakings that have emerged organically in response to a long decade of crisis, upheaval, and war. What new social, spatial, economic, and ecological formations, the experiences of the Ukrainian hardcore inspire us to speculate, may emerge from the rough ground of war?

Moving from the intense and brutal locality of the previous section, in Scratching on things I could disavow we spin the globe. When the imperialist, Occidental anchoring of the world is displaced, purported centers and peripheries become recalibrated and everything starts to shift and multiply (as in Nolan Oswald Dennis’s distinctive globe sculptures, mentioned here in Sean O’Toole’s artist profile). The new “intense proximities” produced by globalized supply chains and labor flows redraw the maps of what was once quaintly termed the global village, as is discussed in Émilie Renard, Claire Staebler, and Mathilde Walker-Billaud’s conversation on Okwui Enwezor’s 2012 Paris Triennale. Yuk Hui examines how the neoliberal order’s favorite lexicon of societal transition, development, and progression under the auspices of free trade rings hollow against a neo-reactionary recurrence in the political centers of the former West, while a conversation on Mohamed Amer Meziane’s new book The States of Earth illuminates how the imperial violence of extractivism and dispossession has become increasingly integral to the functioning of the modern nation state. Curious entanglements and strange networks abound: from nonhierarchical uncuration in a Jakarta biennial to Syria’s post-Assad futures, from Hegelian philosophers-cum-diplomats negotiating international trade deals to arts educators countering the epistemic racism of the global art world.

Tick-tock. In Chronotopes time goes by, as multiple—and often incommensurable— timescales and calendars intermesh with and overwrite one another. Hallie Ayres writes on the human and non-human records of time passing (in recent work by ikkibawiKrrr), Musoke Nalwoga on the real footage of an event and its subsequent reenactment (in Cihad Caner’s work on a 1972 Dutch anti-immigrant riot), and Leopoldina Fortunati on the marked discrepancy between the male proletarian’s hourly waged labor and the housewife’s unremunerated double shift. Questions of longevity and exceptionality are also chronotopic—here seen in Maria José de Abreu writing about the Portuguese experience of life under Europe’s longest-lasting fascist regime—as are the petrofatalist high-speed chases engaged by Y. Malik Jalal’s assemblage work and the “glitch in the imperial clock” that Xenia Benivolski finds throughout Ho Tzu Nyen’s investigations into imperial efforts to control time.

From the shifting sands of the globalized, post-liberal geopolitical order to the post-genomic framework of modern cancer research, increasing orders of complexity bedevil our current epistemologies. In Walls of Complexity, the more we see, the more perplexed we become. Correspondingly, artists, curators, and radical thinkers continue trying to reckon with the situation Aslak Aamot Helm characterizes—in his essay on complexity in the life sciences—as the “valley of undetermination.” Reviewing a recent Hans Haacke retrospective, Jörg Heiser finds the veteran institutional critic forensically mapping the sprawling portfolio of a New York slumlord, while Stephanie Bailey visits a prismatic conference on the deep time of collective struggle staged within an immersive diorama. For Ben Eastham, the sprawling extent of the latest Sharjah Biennial approaches what Ursula Le Guin called the strange realism of our strange reality, while for Juan José Santos the bewildering combination of familiar if incompatible themes in the 38th Panorama of Brazilian Art starts to feel like a “bureaucratic exercise.”

There is a moment in revolutionary time after the old order is deposed and before the Wet Concrete sets. This is an interregnum when the volatile energies of resistance, refusal, protest, and defance have yet to canalize into political organizations or institutions. Dingxin Zhao’s thoroughgoing genealogy of nationalist movements here situates the wet concrete of the French Revolution as the foundations of European liberal nationalism, while Carmen Amengual’s flms look out toward the dimming 1970s horizons of Third Worldist cultural revolution. Tamta Khalvashi and Luka Nakhutsrishvili’s dispatch from Georgia’s ongoing post-election mass protest movement resonates with Tom Allen’s reading of the concluding volume to Peter Weiss’s epic bildungsroman of political refusal, The Aesthetics of Resistance. Henry Giroux ekes out a space for a critical theory of education, while Valeria Graziano, Marcell Mars, and Tomislav Medak extol the swashbuckling, insurgent activity of “pirate carers.” Finally, a pair of reviews from Stephanie Bailey and Kaelen Wilson-Goldie touch on the artistic meditation of more recent instances of defiance, from the Tunis protests that sparked the 2010 Arab uprisings to the 2019 protests against Bolsonaro’s shoot-to-kill policy in Rio’s favelas, against which the syncretic iconography of Antonio Obá’s paintings can be situated.

From the revolutionary desire for a world turned upside down, in We Want Everythingthe Index turns to examine how (as Proust had it) “Desire makes everything blossom; possession makes everything wither and fade.” This process of blossoming and withering holds for speculative economic bubbles like Tulipomania, explored in Charles Tonderai Mudede’s essay on the nascent capitalism of early modern Netherlands. It also holds for the insatiable new needs produced by the advertising industry (as can be seen in Isabel Jacobs’s piece on Radu Jude’s montage of post-communist commercials in Romania: Eight Postcards from Utopia, 2024). Desire blossoms in the experimental eroticism of Sagarika Sundaram’s textile works and the supple paintings of the MuMoToMo collective. Pietro Bianchi finds repressed desires roaring to the surface in the latest remake of Nosferatu from Robert Eggers, while Crystal Bennes writes on Mohamed Abdouni’s subtle meddling with “male homosocial desire” in a family archive. Orit Gat attends the curious exercise in gallery matchmaking that is Condo London, and McKenzie Wark’s thoroughgoing rundown of last spring’s bumper crop of trans literature touches on the entanglement between disappointment and desire, as well as the joyful busting of cis taboos.

Index #7 breathes its last gasp and draws to a close with a section on health, death, therapy, sickness, aging, sclerosis, contagion, and healing. Titled They Are Shutting Off the Lights, here we anxiously observe noxious chemicals sealed in the glass cylinders of Hamad Butt’s metastable sculptures, stroll along the innovative loggia of Filippo Brunelleschi’s Florentine Ospedale degli Innocenti (Hospital of the Innocents), and in Dresden find Kenny Fries writing on misguided curatorial framing of works by disabled artists. Lydia Xynogala takes to the waters in her genealogy of late-nineteenth century hydrotherapy, while Leslie Chapman takes to the couch with an algorithmic shrink, and Yvan Prkachin takes the time to explore the process of bricolage at work in medical innovation. Amica Dall introduces us to burned-out activists, while Franco “Bifo” Berardi takes the salutary example of the United Healthcare CEO shooter Luigi Mangione to parlay between a generation of terminally distracted youth and the systemic, chaotic dementia of a sundowning political order.